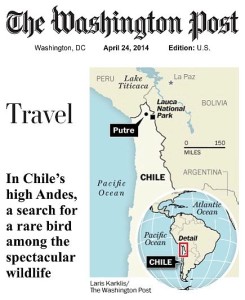

The Washington Post’s journalist mention us. Charles Lane wrote about the area, The Search For A Rare Bird Among The Spectacular Wildlife In Chile’s High Andes, Terrace Lodge.

The Washington Post’s article

“In Putre, our base of operations was Terrace Lodge, a European-style hotel run by an energetic couple from Italy, Flavio and Patrizia d’Inca.

“In Putre, our base of operations was Terrace Lodge, a European-style hotel run by an energetic couple from Italy, Flavio and Patrizia d’Inca.

Terrace Lodge’s five rooms are basic but tidy, equipped with plenty of hot water and big, fluffy comforters to stave off the mountain chill, which can drop to near-freezing at night — even in the August high season, when we visited.

Patrizia serves breakfast, which is included in the room price and typically consists of fresh bread, cheese and one of her homemade oven creations, plus what surely must be the most authentic Italian cappuccino between La Paz and Arica.”

The odd coloring of the rocks, coupled with the overall barrenness of the place, made us feel like visitors to Mars.

Flavio Tourist Guide

“Flavio’s job is to guide you through the national park and its surroundings — and it’s a task he performs both capably and enthusiastically. For a separate fee, ranging from about $100 to $150 per person, he offers a variety of day trips, each limited to no more than four passengers and focused on a particular selection of the region’s natural wonders.

It’s worth it to go with Flavio, because his four-wheel drive carries hot coca tea and an oxygen tank to ward off altitude sickness — and, more importantly, because Flavio is a bona fide expert on regional geography and history. He has an uncanny eye for wildlife, which enables him to spot small, elusive creatures like the huemul — Andean deer — that you might miss otherwise.

Our first jaunt with Flavio took us to the Quebrada de Allane, a deep canyon of red and yellow rock, through which the chilly Lluta River flows on its way from the high Andes to the Pacific. After exploring the canyon rim, we made our way down to the river, where Flavio showed us how to paint our names on some flat rocks using the strange yellow-covered mud that lies along the Lluta’s banks. Though the sun was strong and warm, my son reached into the water and plucked out several chunks of ice, which had apparently been carried down from the higher, colder elevations.

We continued from the Quebrada de Allane to Suriplaza, a broad plateau ringed by red-and-brown mountains nearly 15,000 feet above sea level. The odd coloring of the rocks, coupled with the overall barrenness of the place, made us feel like visitors to Mars. Despite its name — “place of the suris” — we saw no Darwin’s rheas at Suriplaza.

We did find a herd of vicuñas grazing in a bofedal. Once hunted almost to extinction for its precious silken wool, the vicuña has returned to abundance since being placed under government protection by several South American countries in the late 1960s, and Lauca National Park is one of their favorite habitats.

Flavio taught us to distinguish vicuñas from the taller, more robust guanaco, a similarly tawny camelid, which is thought to be the wild progenitor of the domesticated llama — just as the vicuña is the ancestor of the smaller, woolier alpaca…”